Department of Biology

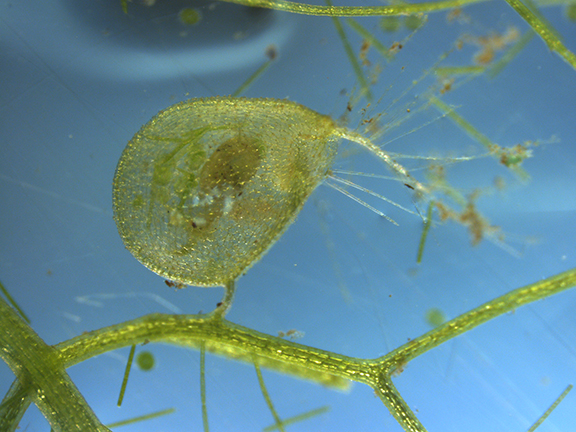

Utricularia australis have no roots; they simply grow at one end and die off at the

other.

The fastest predator known to scientists — is a plant

Dr. Ulrike Muller never set out to study predators. In fact, in high school, she intended to become an artist. But as things turned out, she ended up studying biology, with an expertise in biomechanics. She studies how organisms interact with the physical world, particularly how organisms interact with water to swim and to feed.

“Small organisms are hard to study, not only because they are small, but also because they can be incredibly fast,” she said. “That’s because small means small mass, means low inertia (that's physics for you).”

Right now she is studying the fastest predator known to scientists — it can catch and swallow its prey in less than a millisecond. And yes, it's a plant. A carnivorous plant called bladderwort.

“We study its feeding behavior, how it catches its prey using what is called suction feeding — sucking prey into your mouth from a distance,” she said. “We want to understand how this plant is able to be so fast when animal predators of the same size (fish larvae) struggle to keep up.”

So what have these plants figured out that animals haven't? And why care?

Suction feeding is an important feeding mode. And fish larvae are bad at it, so much so that, in some fish species, 99% of cohort mortality happens at the larval stage.

“Most fish starve to death as larvae because they are unable to catch enough food,” she said. “If we can understand better how suction feeding works, perhaps we can improve feeding success for larval fish, and make a big difference for aquaculture.”

The most accessible part of Dr. Muller’s work is that she uses high-speed cameras a lot.

“Things look amazing when you slow them down,” she said. “And our cameras can slow things down a lot to show how cars crash and how fireworks crack.”

Dr. Muller enjoys studying small organisms, typically a few millimeters in size.

A full professor with a small research lab, Dr. Muller collaborates with researchers across the globe. She is also the co-host of a monthly radio show on science, and an editor-in-chief of a scientific journal. She has been co-hosting a monthly outreach event (Central Valley Cafe Scientifique) for more than a decade, and she hopes to continue once the COVID epidemic no longer makes social events so difficult.

With COVID, teaching has new challenges.

“Since the switch to virtual instruction, I have started to work hard on making my courses function online,” she said. “It's hard to stay motivated as a student in online classes. But it's also neat how it's possible to set your own pace and own hours as a student when an online course is designed well.”

As mentioned earlier, Dr. Muller co-hosts a monthly radio show on public radio, together with Dr. Rory Telemeco and Dr. Alija Mujic in the Biology Department at Fresno State. The program, Science, A Candle in the Dark, is broadcast every fourth Thursday at 3 p.m. on KFCF FM 88.1, Fresno. It features science in the Central Valley.

Dr. Muller collaborates with scientists in Japan, the Netherlands, and in the U.S.

From Germany, Dr. Muller was attracted to science during her years as an undergraduate student in higher education.

“In school, I liked population genetics because it seemed to use a lot of math,” she said. “But then I became aware of biomechanics in my first semester as an undergrad. I liked it because it contains a lot of physics, engineering, and math — the things many biologists don't like. I persuaded an instructor to let me take a grad course in bio fluid mechanics in my freshman year and never looked back.”

Dr. Muller went to England to do her master-level research and to learn English, then went to the Netherlands for her Ph.D.

“I have worked in the Netherlands, England, and Japan before moving to Fresno for this job,” she said. “I enjoy living in new countries, and Fresno the longest I have stayed in one place.”

Dr. Muller finds biomechanics fascinating, but said if she could choose again, she thinks she would study to be an industrial designer, because it blends art and engineering.

But she’s not through learning.

“I have benefited greatly from the expertise and skills that my students bring to our research projects,” she said. “Often students think that they are the learners and I am the teacher. Not so. My research can seem intimidating, especially with all the math and physics it can involve. But I also have projects that stretch well beyond my main areas of expertise into ecology, evolution, engineering, social sciences, science communication, and outreach. So I am always happy to collaborate with my students, and we each benefit from each others' expertise, skills, and interests.”

Achievements with students include published several papers published over the last year with Fresno student co-authors (bold names).

Berg O, Singh K, Hall MR, Schwaner MJ, Müller UK. Thermodynamics of the bladderwort feeding strike—Suction power from elastic energy storage. Integrative and comparative biology. 2019 Dec 1;59(6):1597-608.

Berg O, Brown MD, Schwaner MJ, Hall MR, Müller UK. Hydrodynamics of the bladderwort feeding strike. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A: Ecological and Integrative Physiology. 2020 Jan;333(1):29-37.

Singh K, Reyes RC, Campa G, Brown MD, Hidalgo F, Berg O, Müller UK. Suction Flows Generated by the Carnivorous Bladderwort Utricularia—Comparing Experiments with Mechanical and Mathematical Models. Fluids. 2020 Mar;5(1):33.

Müller UK, Berg O, Schwaner MJ, Brown MD, Li G, Voesenek CJ, van Leeuwen JL. Bladderworts, the smallest known suction feeders, generate inertia‐dominated flows to capture prey. New Phytologist. 2020 Jun 7.

“We have been invited to submit another paper to the journal Fluids (submission deadline March 2021), which will again feature Fresno student co-authors. So more papers are coming soon,” she said.

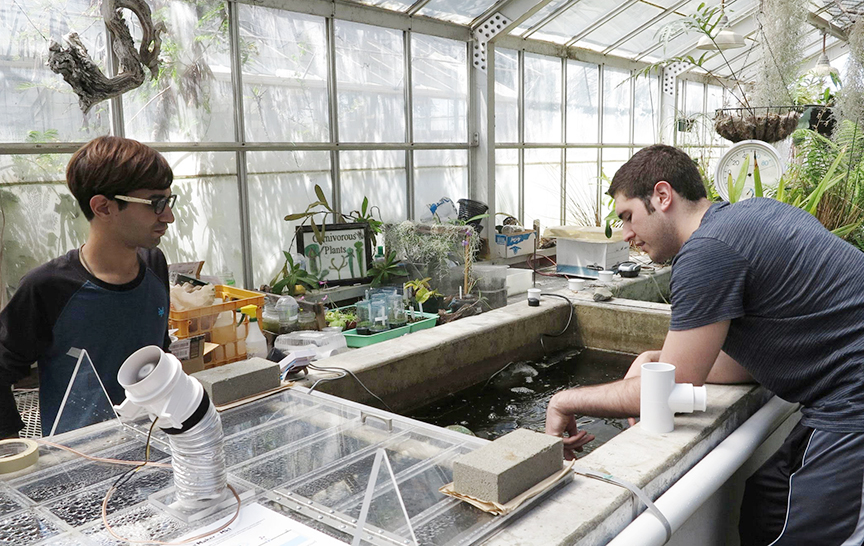

May 26, 2018: Students Eshan Bhardway and Ben Arax in the university greenhouse with the carnivorous

plant culture. In the foreground is the fog mister machine that Eshan built for the

plants.