Department of Biology

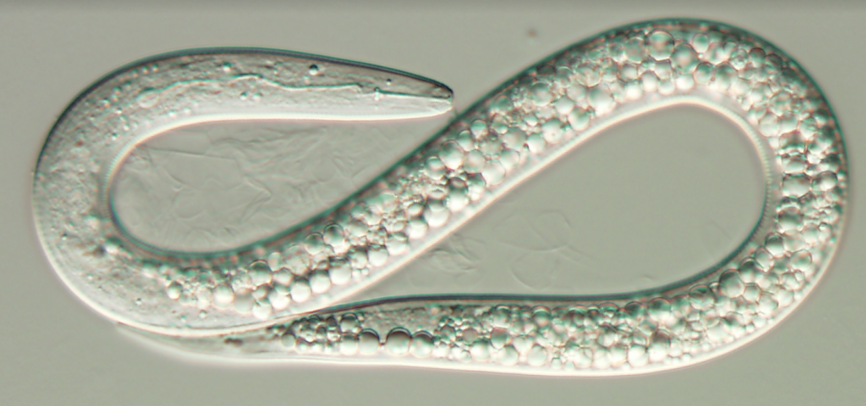

Meloidogyne incognita, a parasitic nematode found in plant crops

Crop failures a thing of the past?

An estimated global loss of $167 billion in crops due to pests takes place every year. But how do you treat the problem, without having a negative effect on the environment?

Innovators Dr. Alejandro Calderón-Urrea and Dr. Brian Tsukimura are addressing these

pest problems. Faculty in the Department of Biology at Fresno State, they have developed

new ways of handling attacks on our food supply. Their work ultimately could impact

society’s food deficits and, conceivably, contribute to eliminating global starvation

— all while taking into consideration the impact on the environment.

Both have intellectual property in the areas of preventing and curing crop pest infestations.

They have already obtained patents for their products — Dr. Calderón-Urrea’s patent

is for a cocktail that addresses plant parasitic nematodes in plant crops, and Dr.

Brian Tsukimura’s patent is for a chemical that reduces tadpole shrimp infestations

in rice fields.

The odds for receiving a patent are fairly low. Your invention has to be unique. Many

applications are rejected on their first attempt, and the odds of gaining approval

go down for each resubmission. Even after a successful filing, it takes about 3.5

years before you receive it.

The chances of getting a product to market are even less likely.

But Dr. Calderón-Urrea’s biotech company is already selling products based on his

patent, and Dr. Brian Tsukimura has had interest in his product from an agricultural

company.

Look at the U.S. Patent Statistics Summary Table, and you will see an astounding number

of patents listed from 1963 to 2019, but how many of these have practical applications

that impact our world, our future?

Agriculture is vitally important, especially here in the Central Valley, but also

world-wide. Crop devastation is a problem that has haunted the world for thousands

of years. Innovators in the Department of Biology know that hunger is very real, and

they are developing practical ways to address crop failure that work long-term.

Dr. Calderón-Urrea has conducted much of the foundational research in the ACU Lab,

at California State University, Fresno with support from many undergraduate and graduate

students. He partnered to create Telluris Envirotech LLC and Telluris Biotech India.

The products they developed can contribute to our local community and to society at

large.

The damage caused by parasitic nematodes attacking plants can cause a tremendous loss

in crops, and his products could significantly increase the productivity of crops

in the Central Valley, as well as around the world.

Dr. Calderón-Urrea’s products are environmentally friendly. Toxicity is not high,

like other products, while the ability of nematodes to build up resistance is low.

Lab tests show the product is not harmful to soil microorganisms and plant health

impacts are low.

“In agriculture, it’s very important to consider how you impact the environment,”

said Dr. Calderón-Urrea. “We have to consider our how we are affecting future generations.”

Also environmentally friendly, Dr. Tsukimura’s product decomposes quickly in water.

It prevents tadpole shrimp from reproducing and slows down their growth, which is

essential, as these invasive pests can grow quickly and reproduce in only 5 to 6 days.

Dr. Tsukimura’s is the first patent known to be issued to faculty at Fresno State.

Several of his graduate students received master’s degrees developing the parts of

the product, and numerous undergraduates participated in its development. The product

was developed from understanding the basic biology of the tadpole shrimp, to make

it the most effective control measure available.  To look at them, you wouldn’t think these small creatures could be so devastating

to a rice crop, but they can knock out 20 percent of a rice crop before the rice seedlings

even put roots down. This is because in their quest for insect larvae and other preferred

food, these carnivores can stir up the mud, ruining a rice crop before it even gets

started.

To look at them, you wouldn’t think these small creatures could be so devastating

to a rice crop, but they can knock out 20 percent of a rice crop before the rice seedlings

even put roots down. This is because in their quest for insect larvae and other preferred

food, these carnivores can stir up the mud, ruining a rice crop before it even gets

started.

In egg or “cyst” form, the tadpole shrimp plaguing rice crops in Fresno and Merced

counties can survive nearly anything. They have been taken to space, returned to earth,

and still, add water, and they hatch.

“Even burning a rice field doesn’t stop them in encysted egg form,” said Dr. Tsukimura.

“They survive in the soil.”

Current products for treatment include copper sulfate, which is harmful to just about

everything in an ecosystem. By contrast, Dr. Tsukimura’s product is an organic compound

that doesn’t even kill the pest — it just controls reproduction.

“Controlling invasive species is always something we want to do, so we can keep their

numbers down,” he said.

Getting food on the table depends on a lot of factors. When your livelihood depends

on producing crops, and you have an infestation, how are you going to find a solution

that works for both you and the environment?

Well, innovators in the Biology Department have some answers. They are coming up with

practical, tangible ways to address agricultural problems that affect everyone's future.

So sit down at your table. With trailblazers like Dr. Calderon-Urrea and Dr. Tsukimura

on the job, dinner is served.